Some Meditations have 2 options, you can choose any of them

Option A

Option B

Download.

Text

From the Cross to the Sepulcher Inclusive – Our Lady of Sorrows

[298]

Jn 19:23–37; Mt 27:35–52; Mk 15:24–38; Lk 23:34–46

Usual Preparation Prayer.

First Prelude: The history: This is the history of the mystery. It is to call to mind how Mary, the Mother of Jesus, stood by the cross on Calvary, and to think of the sufferings she endured. Cf. Jn 19:25 “Standing by the cross of Jesus were his mother and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary of Magdala.”

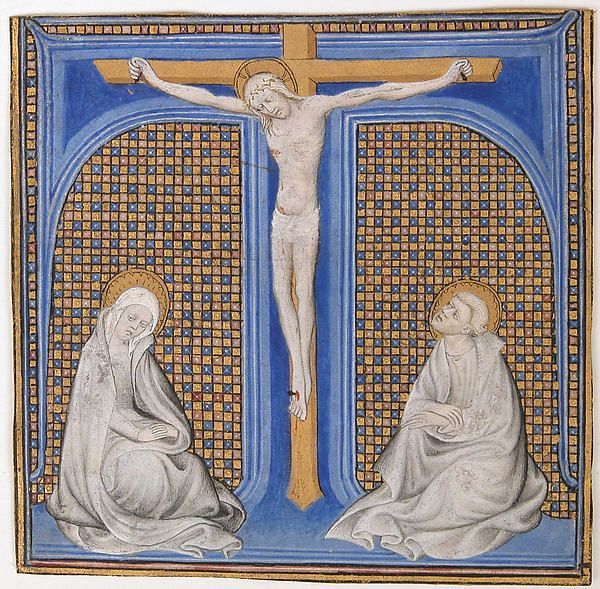

Second Prelude: The composition of place: This is to see the place. Here we can consider the place of the crucifixion, with Mary standing by the Cross.

Third Prelude: The petition: I will ask for the grace I desire. In the Passion it is proper to ask for sorrow with Christ in sorrow, anguish with Christ in anguish, tears and deep grief because of the great affliction Christ endures for me.

As we have already seen, in [298], Ignatius gives us a set of three very simple points to follow, of which we will only concern ourselves with the first:

[298]

First Point

He was taken down from the cross by Joseph and Nicodemus in the presence of His sorrowful Mother.

Likewise, at [208], Ignatius tells us that on the seventh day, we can consider other topics as well, as he writes: “Let him consider, likewise, the desolation of our Lady, her great sorrow and weariness, and also that of the disciples.”

“Does it mean nothing to you, all you who pass by? Look around and see if there is any suffering like mine.” These words from the Book of Lamentations (1:12, NIV) apply perfectly to our Blessed Mother as she stood by the Cross on Calvary. To almost everyone else, her sufferings were nothing, and even those who shared her sorrow couldn’t grasp the depths of her pain. The story is told that Blessed Henry Suso, a Dominican friar, once asked Mary to experience the sorrow our Blessed Mother felt, and Mary simply replied, “My Child, you have no idea what you’re asking.” The saint insisted, however, the grace was granted, and he later recalled that darkness and grief so enveloped his soul that he was unable to eat or drink or sleep. He could say, as we read in the Book of Lamentations, that “he had [even] forgotten what happiness is” (3:17). So overwhelming and oppressive was his grief that Henry worried he would die from it, and so he cried out, asking for relief. At once Our Lady appeared, and he was restored. Turning to Mary, he told her, “Now I understand what you experienced on Calvary.” At that, Mary looked sadder still, and replied, “My Child, what you felt was but a drop of what I felt on Calvary.” Expressing the same truth, with different words, Saint Bernadine of Siena explained “Mary’s sorrow was so great that, even if it were divided among all men and women, it would suffice to cause their immediate death.”

Indeed, it has been said that the Church calls Mary the Queen of Martyrs “because her martyrdom surpassed that of all others. Although her body was not bruised by torturers, her heart was pierced by the sword of compassion for her Divine Son.” St. Alphonsus Liguori once noted quite movingly that Mary suffered in her heart all that Jesus endured in His body. Mary had three loves in her Immaculate Heart: God, her Son, and souls. She so loved the world that she gave her only Son. As St. Bernard said, “The sword would not have reached Jesus if it had not pierced Mary’s heart.” Mary loved souls and on Calvary, after suffering such cruel torments she merited being the mother of all mankind.

It is this sorrow, which is truly beyond our comprehension, that we are trying to grasp at least a part of. We can consider three reasons why Mary’s sorrow is so great: first, who Mary is in relation to Jesus, second, the way time passed, and third, the sufferings themselves of the way of the cross and of Calvary.

First, we know that Mary is the Mother of God; Christ took His human nature from her. What is human in Jesus comes from Mary. In a sense, the Immaculate Heart contained the Sacred Heart, and for nine months it was under that Immaculate Heart that the Sacred Heart was protected, sheltered, and clothed in flesh. More than anyone else, Mary could say that Christ was “bone of her bone, and flesh of her flesh” (Gn 2:23).

We can think of how she saw that flesh as Christ made His way to Calvary. At His birth, Mary held the Savior in her arms, as she would do so many times in the future. She would caress His sacred Head, hush His cries, make and wash His clothes, and attend to His every need. The weight of those memories is unbearable as she sees Him now, His sacred Head caressed by a Crown of Thorns, His “throat, parched as clay,” unable to utter a cry, His clothes, torn, bloodied, and to be gambled for, and, in His agony, His burning thirst, His bitter anguish, she is unable to do anything at all to alleviate His sufferings. Mothers suffer more at the sight of their children’s sufferings than if they had those torments inflicted on themselves. For a mother so dear and so tender, who loved Christ more than anyone before or since, there is no greater agony than to see Him suffer, and be unable to alleviate His pain in any way. Even the last consolation, of having Him “breathe His last in her arms” (Cf. Lam 2:12) was denied her. She could only look on and wait.

The Blessed Mother would’ve returned in her heart to that prophecy that had now been so brutally fulfilled: “Behold, this child is destined for the fall and rise of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be contradicted, and you yourself a sword will pierce so that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed” (Lk 2:34-35).

Simeon predicts a “sword” piercing Mary, although a lance would seem to be a better image since it would parallel what happens to Christ on Calvary. The reason lies in the very specific word Luke uses here for sword. Throughout the New Testament, the word translated into English as sword is almost always μάχαιρα (makh’-ahee-ra), the standard short sword used by the Romans legionaries. However, in Simeon’s prophecy, he speaks of a different sword, a ῥομφαία (hrom-fah’-yah) piercing Mary; that word is used only here, in this passage from Luke, and in the Book of Revelation, where it shows forth the overwhelming power of God’s word. This is the “two-edged sword came out of [Christ’s mouth]” (Rev 1:16). Let us think, for a moment, of the power of those words: Psalm 29 tells us that the “voice of the LORD cracks the cedars; [it] strikes with fiery flame; the voice of the LORD shakes the desert and strips the forests bare.” When John needs to convey that power, that force, it uses that same sword that pierces Mary’s heart. This gives us at least a glimpse of what hit Mary’s heart: that sword cracked her heart, struck it with fire, shook it, and stripped it bare, of everything that she held dear.

The word Simeon uses, then, refers to a sword so large and imposing that the ancients considered it a javelin or a spear rather than a sword; we might say, in a sense, that Simeon does say that Mary will be pierced by a lance. The sword was double-edged and both cut and pierced; it was such an imposing weapon that the word for it took on the symbolic meaning of “war” and “piercing grief.” Although the short sword was imposing, the broad sword of which Luke speaks was much more damaging and cut through any sort of defense. If anything could cut through barriers and reveal what lay hidden, this sword would do it. There is, therefore, no sorrow, no suffering, more imposing than that inflicted on the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Simeon’s prophecy refers to how the crowd’s response to Mary’s sufferings that rent her heart reveals their attitude towards Jesus Christ her Son. Although the Pharisees might have been indifferent to Jesus’ sufferings on the cross, they should at least have had compassion on His Mother. Their hardness towards her refers their indifference to God Himself.

Simeon’s words point out something else: a lance can be thrown from afar, and so the one who causes the hurt can be at a distance. But to be pierced with a sword, means being near to the one who causes the wound. Physically, spiritually, emotionally, there was no one closer to Jesus than Mary, and hence no one was more wounded by His sufferings than she.

Mary’s thoughts must have returned to the Temple in Jerusalem, when Jesus was lost to her for three days. That experience was the closest one Mary had to sin, since, being sinless, she never lost Jesus in her soul.

But, she had never let go of that experience: Luke cryptically tells us that after the event took place, “his mother kept all these things in her heart” (Lk 2:51): all these things, all of them, not letting a single one of them escape. The Greek word emphatically means “to keep thoroughly intact and together.” She held tightly to that anxiety, as she said, “Your father and I have been looking for you with great anxiety.’” That word anxiety has been rendered in other versions as sorrowing (KJV, DRA), anxiously (RSV), or with heavy hearts (GNV). That’s because the Greek ὀδυνώμενοι (odynōmenoi) encompasses all these meanings, since, as one concordance has it, it means “to experience intense emotional pain, i.e. deep, personal anguish expressed by great mourning; this sorrow is emotionally lethal if experienced apart from God’s grace which comforts. This root (ody-) literally means ‘go (as the sun in a sunset – cuando el sol se pone al ocaso) and refers to consuming sorrow.” That loss in the Temple, with its consuming anxiety, was but a mere foreshadowing, the barest anticipation, of the consuming sorrow that would set on Mary, just as the stone enclosed Christ’s Body in the darkness of the tomb.

Thus, the agony and anxiety of those three days, searching for the lost Savior, must have returned to her now, but with the profound difference that now there was no hope of finding Her Son alive and well; this loss was definitive, the sentence issued and executed, and there would be no reprieve. This time, when her Son is lost for three days, she will know exactly where to find Him.

Likewise, her mind must have returned to the mysterious raising of the son of the widow of Nain (Lk 7:11-17), the only miracle Jesus performed without being asked. Jesus saw the dead man, “his mother’s only son, and she was a widow,” just like Jesus and Mary. Moved by compassion for her, Jesus raises the son, but only after telling her “Do not weep,” an even more compassionate gesture for a woman who had no hopes of seeing her son alive again. Did Mary catch a glimpse then of what awaited her, a widow whose only Son would also be carried away? Yet, all she has is the echo of those words in her memory accompanied by an unbearable silence. For the widow of Nain, there was comfort, for the widow of Nazareth, nothing.

Indeed, those words, “Do not weep,” echoed in her memory on Calvary and after the burial of Christ, since even tears would have been no relief. Saint Ambrose notes that in John’s Gospel, there is no mention of Mary’s tears, even though John records the tears of Jesus, the sisters of Lazarus, and others. “I read that she stood,” he writes, “but I don’t read that she wept.” And there’s a reason for this: Aquinas tells us that crying is a remedy for sorrow, but for Mary, those tears would have been to no avail; her sorrow was beyond remedy, beyond tears. “A hurtful thing hurts more if we keep it inside,” Aquinas writes (ST, I-II, q. 38, a. 2, corpus). Instead, Mary “pondered these things in her heart,” as if that grief was too great a burden to impose on anyone else.

Taken down from the cross, she could look one more time into Jesus’ eyes, the only fitting mirror for the One who was conceived without sin and whose beauty far surpasses that of the angels. Yet, those dim eyes could not return her gaze, and she was met only with the stony silence of death.

“Once again Jesus lies in her arms, as he did in the stable in Bethlehem (cf. Lk 2:16), during the flight into Egypt (cf. Mt 2:14) and at Nazareth (cf. Lk 2:39-40).”[1]

Secondly, Mary’s sorrow was amplified even more because of how the time passed. Time spent with the Beloved goes quickly: Genesis 29:20 tells us that Jacob worked “seven years for Rachel, but to him they seemed as but a few days, since he loved her.” Likewise, the saints can pass hours in ecstasy, and to them it seems but a few minutes.

Consider, then, how time must have dragged on for Mary, since she lived her entire life in the presence of Christ, and now she was deprived of it. We can catch a glimpse of this in Psalm 90, in that mysterious phrase that tells us “a thousand years in God’s eyes, are merely a day gone by.” How slowly time must have passed for Mary. After living in Christ’s presence for so long, to lose Him to death meant being plunged into the paralyzing atrophy of the passage of time. It would be comparable to being pulled from heaven, to be cast down to earth and the weariness of time. The seconds seemed like minutes, minutes like hours, hours like days, and the days like an eternity. All of this, in a constant and overwhelming sorrow that seemed endless, like the time it was endured in.

Lastly, with all these things in mind, we can consider what it was that Mary endured as Christ went the way of the cross. Imagine their meeting on the Via Crucis: “This Mother, so tender and loving, meets her beloved Son, meets Him amid an impious rabble, who drag Him to a cruel death, wounded, torn by stripes, crowned with thorns, streaming with blood, bearing His heavy cross. Ah, consider, my soul, the grief of the blessed Virgin thus beholding her Son! Who would not weep at seeing this Mother’s grief? But who has been the cause of such woe? I, it is I, who with my sins have so cruelly wounded the heart of my sorrowing Mother! And yet I am not moved; I am as a stone, when my heart should break because of my ingratitude.”

“Look, devout soul, look to Calvary, whereon are raised two altars of sacrifice, one on the body of Jesus, the other on the heart of Mary. Sad is the sight of that dear Mother drowned in a sea of woe, seeing her beloved Son, part of her very self, cruelly nailed to the shameful tree of the cross. Ah me! how every blow of the hammer, how every stripe which fell on the Savior’s form, fell also on the disconsolate spirit of the Virgin. As she stood at the foot of the cross, pierced by the sword of sorrow, she turned her eyes on Him, until she knew that He lived no longer and had resigned His spirit to His Eternal Father. Then her own soul was like to have left the body and joined itself to that of Jesus.”

“Consider the most bitter sorrow which rent the soul of Mary, when she saw the dead body of her dear Jesus on her knees, covered with blood, all torn with deep wounds. O mournful Mother, a bundle of myrrh, indeed, is thy Beloved to thee. Who would not pity thee? Whose heart would not be softened, seeing affliction which would move a stone? Behold John not to be comforted, Magdalen and the other Mary in deep affliction, and Nicodemus, who can scarcely bear her sorrow.”

“Consider the sighs which burst from Mary’s sad heart when she saw her beloved Jesus laid within the tomb. What grief was hers when she saw the stone lifted to cover that sacred tomb! She gazed a last time on the lifeless body of her Son, and could scarcely detach her eyes from those gaping wounds. And when the great stone was rolled to the door of the sepulcher, oh, then indeed her heart seemed torn from her body!”

As our Lord told one saintly soul: “My daughter, the tears which you shed in compassion for My sufferings are pleasing to Me, but bear in mind that on account of My infinite love for My Mother, the tears you shed in compassion for her sufferings are still more precious.”

“Does it mean nothing to you, all you who pass by? Look around and see if there is any suffering like mine.” Let us stay with Mary, so we might not hear the words of Lamentations, “She was left without one to console her, out of all her dear ones” (1:2).

We can end with a colloquy, standing with our Lady at the cross, asking for the grace to imitate her Son, to love Him and to follow Him all the days of our lives, so that His sacrifice, and hers, might not be in vain.

[1] Saint John Paul II, Way of the Cross, 2003.

Take, Lord,

and receive all my liberty, my memory, my understanding, and my entire will, all that I have and possess. Thou hast given all to me. To Thee, O Lord, I return it. All is Thine, dispose of it wholly according to Thy will. Give me Thy love and Thy grace, for this is sufficient for me.

(Spiritual Exercises #234. Louis Puhl SJ, Translation.)